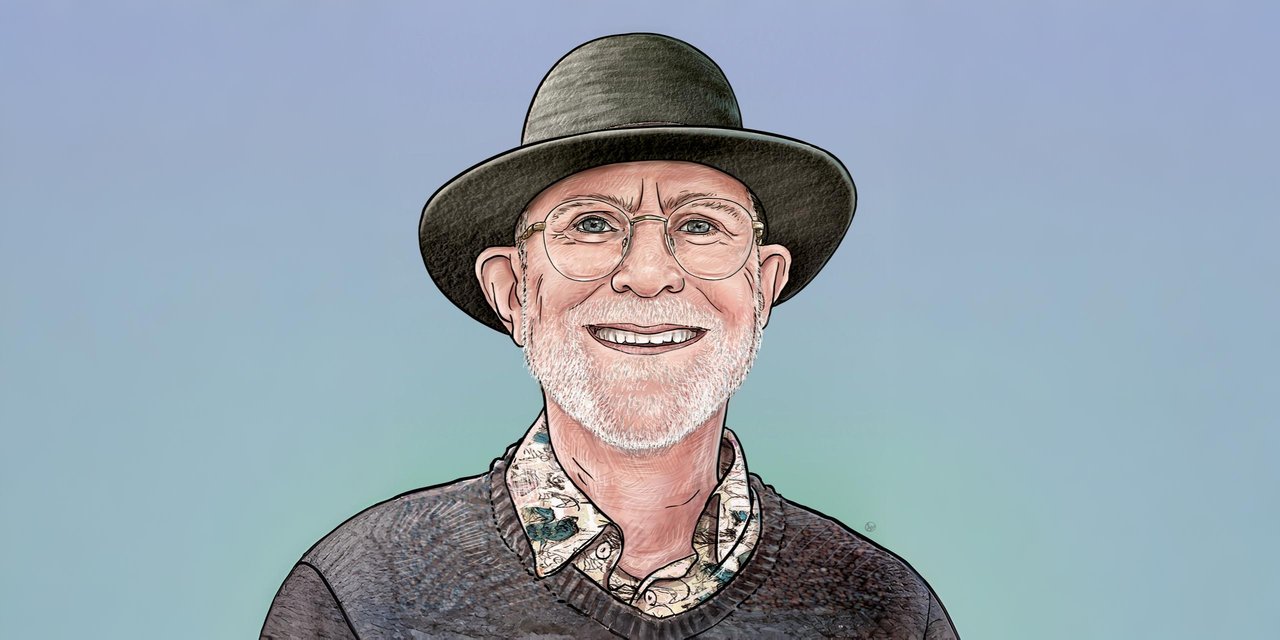

© Scott Marshall

Brave New Bullshit with Phil Wadler

by Elizabeth Polgreen — 8 August 2025

Topics: Interview

Philip Wadler is a man who wears many different hats. Both literally: fedoras, trilbys, even the occasional straw hat, and metaphysically: recently retired Professor of theoretical computer science at the University of Edinburgh; Fellow of the Royal Society; senior researcher at the blockchain infrastructure company IOHK; Lambda Man; often-times favourite lecturer of the first year computer science students; and, occasionally, stand-up comedian. It is the latter role that leads me to ask Phil if he will participate in a Q&A.

As a pre-eminent programming languages researcher, who, perhaps most famously, introduced type classes and monads to Haskell, and contributed to the design of generics in Java, Phil might not be the first person you would expect to start adding to the discourse on AI. Yet, recently, Phil has been delivering a series of talks on large language models. I ask him how this came about and he swiftly deflects the blame. “It’s Conrad Watt’s fault!”, he says. “He invited me to give a talk at Peterhouse College in Cambridge, as part of a series on trust, and I thought ‘Trust? Everybody’s going to want to know about AI. I’m not an AI person, how can I talk about this?’”

“Then I realised that I learned my whole field from John McCarthy, who is an AI person. McCarthy used to say that AI is like Philosophy. Science started out as “natural philosophy”, and then as we understood better, it became physics and chemistry and biology. Similarly, what we now call programming languages or formal methods started out as part of AI. So, in some sense, I am an AI person.”

“And since AI [in the sense of deep learning] is, all of a sudden, very important, I decided to educate myself about it. One of my skills is communicating, and so I’m trying to communicate this to a wider group of people. One of the ways I am doing this is performing a stand-up comedy show at the Edinburgh Fringe [the world’s largest performance arts festival, held every August in Edinburgh] (which is only 50 people at a time, so maybe not the most effective way of communicating!).”

I have seen the fringe show, and I recommend it. Perhaps I am not the target audience, as someone who already works in computer science and is already sceptical about large language models, but I enjoyed it, and it is pitched in a way that ensures the appeal should stretch beyond academics.

In Phil’s words, the key part of the show is the introduction of a new piece of terminology for the output of large language models (LLMs). One of the issues with LLMs is that they often produce incorrect statements, called “hallucinations”. This term comes from computer vision research, where it refers to a vision system identifying something in an image that is not there, literally fitting the dictionary definition of hallucination (“a perception of something not present”). However, as Phil points out, “in the field of LLMs, this is much less appropriate because LLMs are not perceiving anything”.

So, what is the term Phil would prefer us to use? “Bullshit!”

I am doubtful that “bullshit” is a technical term, but Phil assures me otherwise: “If you look it up in the dictionary, bullshit is language spoken to convince somebody, without regard for the truth. And why is this technically appropriate? Consider how large language models are trained: you give them a huge corpus of text like the entire internet, and then you train the neural network so that, if it sees all the words up to a given point, it predicts the next word. The nice thing about this is that you don’t need any labels for your data, so, unlike training neural networks for image recognition, you don’t need any human intervention to make the training data. But what that means is that it is not trained on what is true. Nobody has labelled the text statements with “true” or “false”; it’s all just language. Of course, a lot of what you read on the internet is true, so there will be a correlation with the truth, but technically, there is no regard for the truth in the training data.”

The use of the term bullshit for LLM outputs has emerged independently in several places, including the textbook by Bergstrom and West, which is freely available online, and a paper by Hicks et al., from the University of Glasgow, titled “ChatGPT is Bullshit”.

Of course, one potential issue with using the word “bullshit” is that you might automatically then assume that LLMs are useless, but that isn’t the intention. “I do still think LLMs have the potential to be useful. I want to popularize the use of the word bullshit as a perspective that can help you interpret the information you are getting from the LLM, and can help you to remember that what it is saying needs to be checked through other sources.”

Given the recent discussion in the media about the existential threat of AI, including a petition signed by many leaders of the field, including Sam Altman, Demis Hassabis, and Geoffrey Hinton, stating that AI poses a threat on the same level as nuclear weapons, Bullshit Bots sound surprisingly unthreatening. Is Phil worried about AI becoming more intelligent than us? “I’m not going to say that’s not going to happen, I think that’s overstepping myself to try to predict that, but my own personal estimate is that it’s not a huge threat. But also, more importantly, that there are lots of short-term threats and we should not let the fear of a bigger threat get in the way of understanding all the current threats of what these systems might do.”

The fear of AI becoming more intelligent than humanity, and going against our wishes and harming humans (the classic example being the paperclip maximiser, where an AI designed to make as many paperclips as possible realises that it would be much better if there are no humans, because humans might decide to switch it off and then there would be fewer paperclips) is often referred to as the AI alignment problem, because it involves AI being misaligned with human goals. Phil categorises the list of threats he is most worried about as something different. “You don’t need to resort to science fiction to find powerful entities that are not aligned with the goals of the rest of society,” he says. “They’re called corporations, and they are burning up the world. I think we should spend more time worrying about the alignment problem of capitalism.”

One such threat Phil is concerned about is AI taking away people’s jobs. “People are losing their jobs now. For example, we’ve seen systems like MidJourney or Dall-E do an amazing job of producing illustrations from a description, and there are illustrators who have already lost their jobs to this stuff.” He lists a series of other creative jobs which are all also under threat or potentially under threat in future, including screenwriters, voice actors, and even influencers.

Authors are similarly at risk. “A couple of years ago, Jane Friedman, a successful author who publishes her own books (ironically, books on how to write books), found a bunch of books on Amazon under her name that were pretty clearly written by AI. She only managed to get Amazon to take these down after speaking out on social media and getting covered in the press.”

Perhaps what makes these jobs susceptible is that being a “bullshitter” may not even be a disadvantage in these jobs. “What do you call someone who draws a picture of something that’s not there? A bullshitter? No, you’d call them an artist. So, for many applications of LLMs, it doesn’t matter that it doesn’t have a model of truth.”

Society, however, would be much worse off without people in these roles. “One concern I have is that it will become very hard to earn a living as an author, or a content creator, and we might reach a point where we simply don’t have any authors, or screenwriters or illustrators anymore because they can’t make a living doing it.”

As to how we mitigate the alignment problem of capitalism? Regulation! “It has been widely accepted that we don’t regulate tech very much, and if you regulate, you might be getting in the way of innovation. But look at cars; imagine what cars would be like if they weren’t regulated. You wouldn’t be able to trust getting into a car the way that you do now!”

Specifically, Phil brings up copyright law and how essential copyright is for creatives (including programmers). “In the UK, there has been a lot of discussion about copyright law, and whether companies implicitly have permission to train off any public material, unless the creator explicitly opts out. I was involved in putting together the UK Computing Research Committee response to this, and our stance is that opt-out is terrible (not least because there’s currently no mechanism in place to actually opt out), but we think that opt-in could be a good idea because it would be in the interests of the firms building the LLMs to convince people to opt-in, for instance by paying them sufficiently well to do so. I think it’s really crucial that we, as a society, keep going back to lawmakers and saying that this is really important! Creatives need copyright!”

“We also need to up our game as a society and push for more protection for workers. Ever since Reagan and Thatcher, protections for workers have been slowly ebbing away. With powerful unions, when there were improvements in productivity, the benefits were shared across the whole population. Now we don’t have powerful unions, so what happens is that whilst we have seen increases in productivity, salaries in real terms have flatlined or decreased. This is, of course, all very hard to organise, because all of these powerful firms have much more influence in our media and our politics than the people arguing for these changes.”

So the future of AI is politics? “I think that probably is the case, and I’ve always, throughout my life, tried to educate myself about politics, but I’m not an expert. Essentially, what I’m saying is don’t listen to me!”

If you want to disregard his advice and continue listening to him, Phil is performing as part of The Provocateurs at the Edinburgh Fringe on the 17th and 19th of August and at the Royal Society of Edinburgh on the 7th of September. Or, if you want to heed his advice and listen to someone else, Phil’s book recommendations are below:

- The Bullshit Machines, Carl T. Bergstrom and Jevin D. West, https://thebullshitmachines.com, 2025.

- Power and Progress, Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, Public Affairs, 2023.

- Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age, Vauhini Vara, Grove Press, 2025.

- The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff, Profile, 2019.

- Supremacy, Parmy Olson, Macmillan, 2024.

- Code Dependent, Madhumita Murgia, Picador, 2024.